History & Culture

How Amateur Astronomy Has Evolved

Amateur astronomy has changed drastically over the past couple hundred years, but it’s always encouraged people to look up.

By Briley Lewis

NPS/Jacob W. Frank

For many people, their first experience with a telescope is from their friendly neighborhood astronomy club. These groups host outreach events at schools and other public locations across the country, letting kids and adults alike step up to see the glorious rings of Saturn with their own eyes through a hefty and portable backyard telescope.

Of course, amateur astronomy groups are more than just stargazing clubs. There are amateur astronomy groups in every state — and across the globe — that provide a sense of community for space-interested folks, doing impactful local science communication and even contributing to scientific discoveries. They cultivate an interest in astronomy, for some inspiring careers and for others a great hobby, or at least a greater appreciation for the universe. Although they seem ubiquitous today, where did these groups come from? And why is there this divide between “amateur” and “professional” astronomy?

The title “amateur astronomer” generally refers to someone who observes or studies the sky, but not as their career; the latter are “professional astronomers.” Some amateurs known as recreational observers observe the sky as a fun outdoor activity, and others, known as avocational astronomers, delve deeper and work to contribute to science. Yet, astronomy has existed and been a part of human life since our origins — back when there were no such distinctions between amateurs and professionals, and when people just wanted to look up.

Children and adults alike enjoy observing through a telescope at a star party.

[NPS/Michael Quinn]

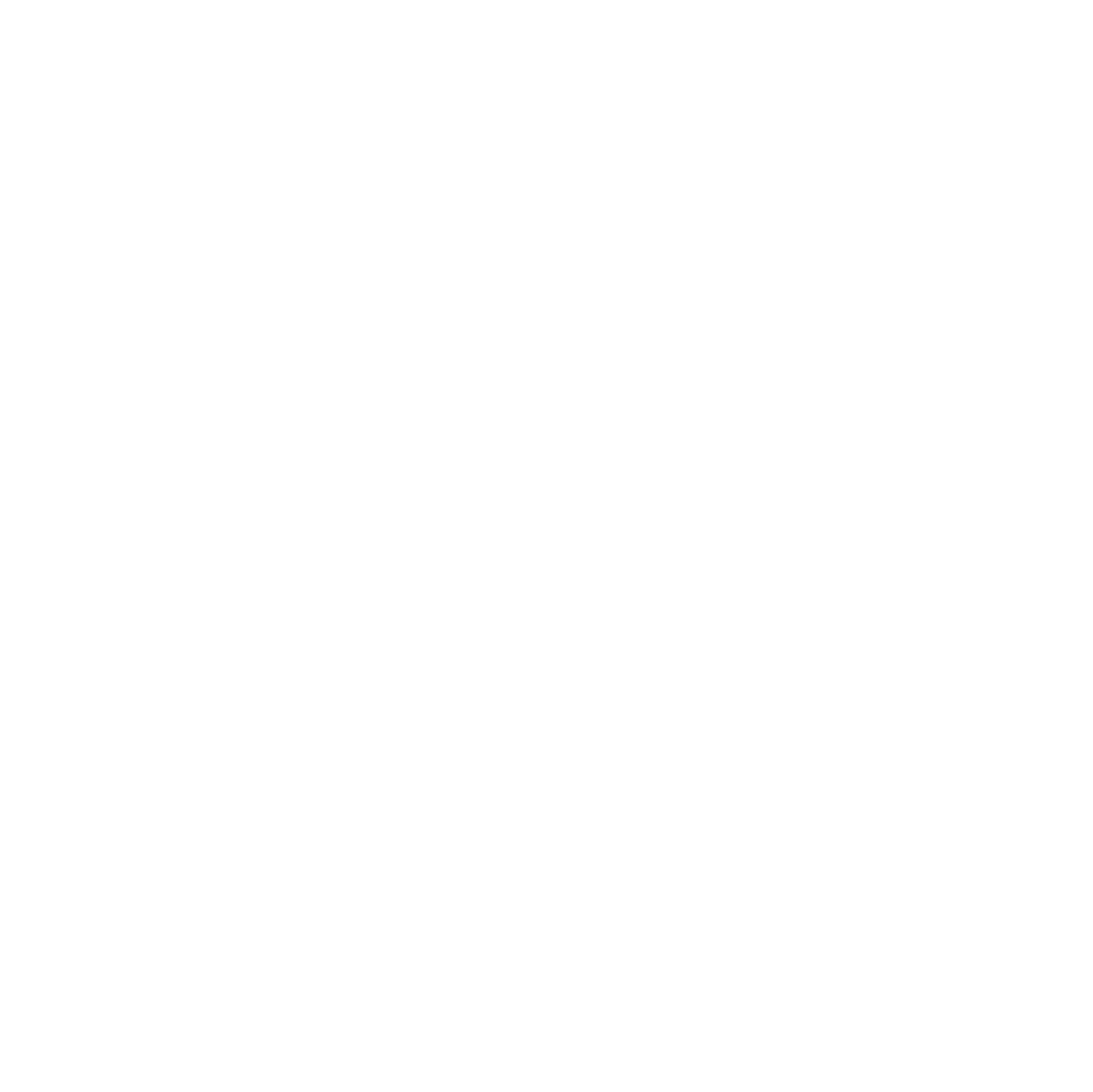

William Parsons, known as the 3rd Earl of Rosse, was one of the “Grand amateurs” of astronomy. With his 72-inch-wide telescope, he observed the spiral nature of galaxies — although at that time, no one knew they were galaxies, but instead thought they were nebulas.

[AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives]

Divisive associations

During the 1800s in Victorian England, divisions between astronomy communities arose due to who had money for the biggest and best equipment, and who didn’t. Some researchers were supported by the state, but many more — known as “Grand Amateurs” — were wealthy, educated men with an interest in the sciences who ended up building many of the major telescope facilities of the time. These wealthy amateurs often had the best telescopes and equipment, even better than professionals — a situation entirely unlike what we see in modern times. Meanwhile, well-off middle-class men began to see astronomy as a hobby, and started buying observing guidebooks and smaller telescopes to use at home. These hobbyists formed clubs to talk about their interest in observing the sky, creating the first amateur astronomy clubs.

For much of the Victorian era, amateur astronomers were an active and vibrant part of Britain’s major organization for astronomers, the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS). That is, until professional astronomers took over the organization in the 1870s and began ousting the amateur contingent in the society. In response, British amateur astronomers created the British Astronomical Association (BAA) in 1890, a group dedicated to involving and supporting amateurs in astronomical research. This group became a space for professionals and amateurs to interact, drawing in big names of the time like Sir Arthur Eddington, stellar astronomer and the namesake of the famous Eddington limit of stellar brightness, and Edward Walter Maunder, a sunspot scientist best known for the Maunder Minimum of the Sun’s cycle. With the BAA prospering, amateur astronomers accepted the loss of the RAS to the professionals.

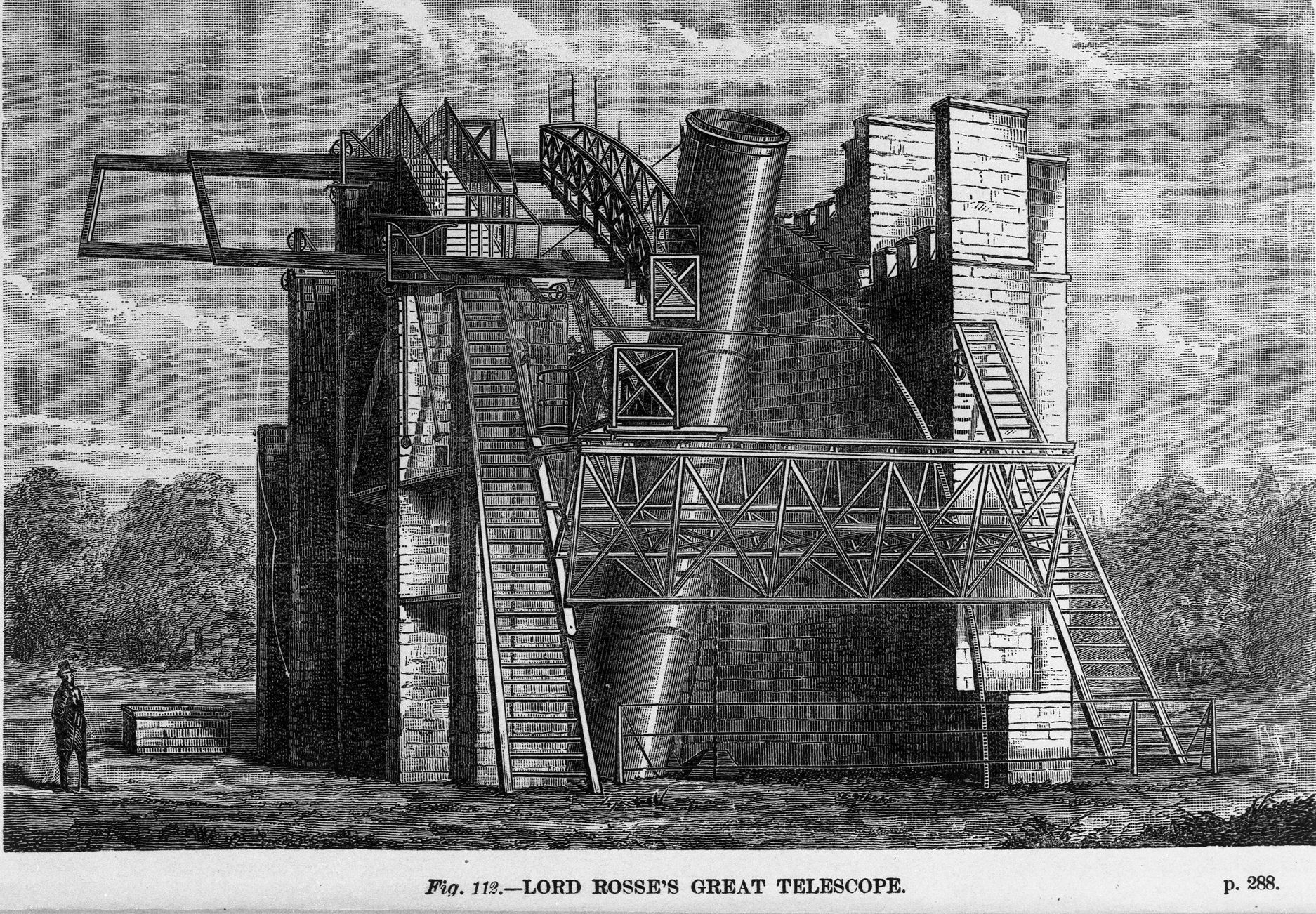

The amateur community in the United States, on the other hand, followed a different path. At the start of the 19th century, the U.S. hosted no major observatories nor had any established astronomy societies. With the support of politician (and eventually president) John Quincy Adams, universities and colleges accelerated American astronomy in the mid-1800s, opening observatories with some of the largest telescopes in the world. People supported observatories much like they would museums, with public support and patronage. This boom in astronomy created a lot of jobs, more than could be filled by formally educated astronomers. Shortly after, wealthy benefactors were supporting observatories and even enticing hobbyists, offering monetary rewards for new comet discoveries in the wake of the spectacular Comet 1P/Halley flyby of 1910.

Between employment opportunities and ample support for new discoveries, amateurs and professionals were intertwined and intermixed. Even with these collaborations between 1850 and 1920, there were still bubbling tensions paralleling those in Britain.

The 1910 appearance of Comet 1P/Halley sparked great interest in astronomical observing, as shown in this illustration of Londoners looking for the comet.

[artist: G. D’Amato; courtesy Library of Congress]

The Astronomical Society of the Pacific was the first American astronomy organization. This photo captures its start at the January 1, 1889, solar eclipse.

Astronomical Society of the Pacific

American amateurs

While American astronomers were doing groundbreaking science and had the respect they needed from their scientific peers abroad, they lacked a successful society. During these decades, organizations (many unsuccessful) popped up as attempts to bring the community together.

The Astronomical Society of the Pacific (ASP), founded in 1889, was the first national astronomy organization in the U.S. serving both professional and amateur astronomers, and it still stands now in 2023. A few regional iterations of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) also blinked into existence in the late 1800s, until the organization we know today was successfully established in 1899 under the leadership of famous comet-discoverer George Ellery Hale. Within the fledgling society, though, there was a debate on whether to include amateurs; one astronomer, James Keeler, went as far as to say the AAS should be only for “those who are capable of accomplishing something in astronomy.”

In the early 1900s, an American imitation of the BAA came into existence to cater directly to amateurs — known as the Society for Practical Astronomy (SPA). However, it was undercut by a lack of funding and a loss of leadership to other specialist organizations, like the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), founded in 1911 and still operating. With the downfall of the SPA, amateurs involved in specific sub-fields flocked to specialist groups that wanted amateur participation, like the American Meteor Society (AMS), founded in 1911, and later the Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers (ALPO), founded in 1947.

Unfortunately, if amateurs weren’t interested in these specific topics, they really had nowhere to turn — and with increasing amounts of education needed to be a professional astronomer, opportunities to get involved became scarcer. Despite the setbacks for amateurs, astronomy in the U.S. only grew in popularity as the professionals made monumental discoveries at observatories atop Californian mountains.

Lick Observatory, shown in this restored 1902 photograph, sits atop one of those California mountains that helped push forward American astronomy.

[Library of Congress/Detroit Photographic Co.]

Members of the Springfield Telescope Makers displayed several of their club telescopes and mirrors at the 1922 county fair.

[courtesy of Springfield Telescope Makers]

How optics ties in

Amateur astronomy groups flourished as telescope-building and the specialty technology to build those instruments evolved. American amateur astronomers soon found their niche in telescope making from 1920 to 1945. Telescope-making meetings provided a space for amateurs to mingle and build connections, providing a foundation for future amateur astronomy groups.

Refracting telescopes were still a rich man’s game, since crafting the precise lenses to refract, or bend, incoming starlight was a costly and painstaking affair. Some enthusiasts turned to reflecting telescopes. Whereas refracting telescopes direct light through a series of lenses, reflecting telescopes rely on mirrors to bounce light around. Those mirrors are a whole lot easier to make and the final products are much lighter weight, so these types of telescopes rose in popularity.

Architect and explorer Russell Porter popularized homemade reflecting telescopes, teaching a group of friends how to make their own and even writing an article for Popular Astronomy called “The Poor Man’s Telescope” in 1921. Porter’s work was later picked up by Scientific American, and readers were hooked. One 1926 issue of Scientific American noted in regard to the amateur telescope making movement, “Evidently, we have ‘started something.’ ”

(At the same time, professional astronomers were switching to reflecting telescopes as well, like the 100-inch telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory and the 200-inch Hale Telescope at San Diego County’s Palomar Observatory. Several news-making discoveries were observed at those instruments, including Edwin Hubble and Milton Humason’s discovery that the universe is expanding.)

With more telescopes available to the public, or at least those with time and the skill to build one, interest in astronomy grew. Telescope makers, led by the Springfield Telescope Makers group, hosted the first national convention for amateurs in the 1920s, known as Stellafane. (The convention celebrates its centennial this fall.) Amateur astronomy clubs — including some still around today like New York City’s Amateur Astronomers Association (AAA) and the Los Angeles Astronomical Society (LAAS) — continued to pop up around the country as interested hobbyists found one another.

World War II also brought a huge investment into optical technology, with new manufacturers recruiting amateur telescope makers and astronomers to help the war effort. In the commercial boom following the war, manufactured telescopes became widespread and their costs dropped. A teenager could buy one on savings from a summer job. Unlike the pragmatic designs of the amateur makers, now a family had abundant optical-design choices: Newtonian reflectors, Schmidt-Cassegrain reflectors, different mounts, different diameter sizes, you name it.

In his dissertation focusing on 20th-century popular astronomy, science historian Gary Leonard Cameron wrote that “between 1940 and 1960, the number of astronomy clubs in America quadrupled,” from around 60 to over 220, with at least one in every state. And during that time, they broadened their membership, involving women and kids as well. Amateurs also finally had a larger national organization, the Astronomical League, founded in 1941, to join them together and hold large yearly meetings. Cameron, in his work, also wrote, “the rapid increase in the popularity in amateur astronomy coincides so well with the development of inexpensive telescopes in America that it is difficult to believe the two are unrelated.” This proliferation of the hobby was the beginning of a shift away from amateurs as purely serious scientific contributors, and instead focused on recreation and enjoyment of the night sky.

Telescope maker Russell Porter worked on this 2.5-inch-diamater telescope with his young daughter Caroline. She ground the mirror between 1919 and 1929.

[courtesy of Springfield Telescope Makers]

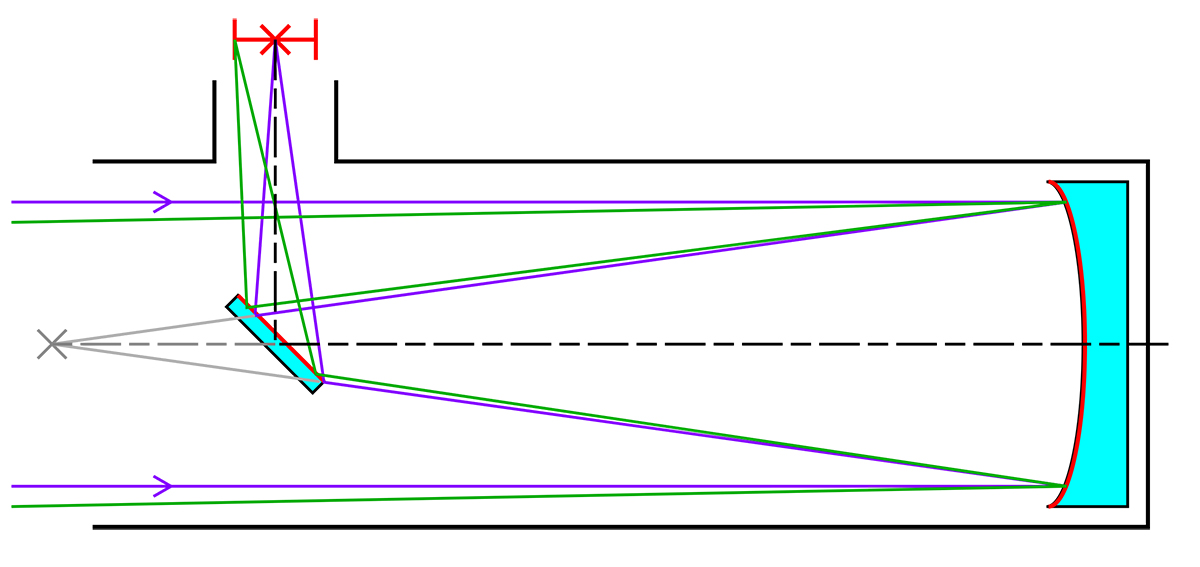

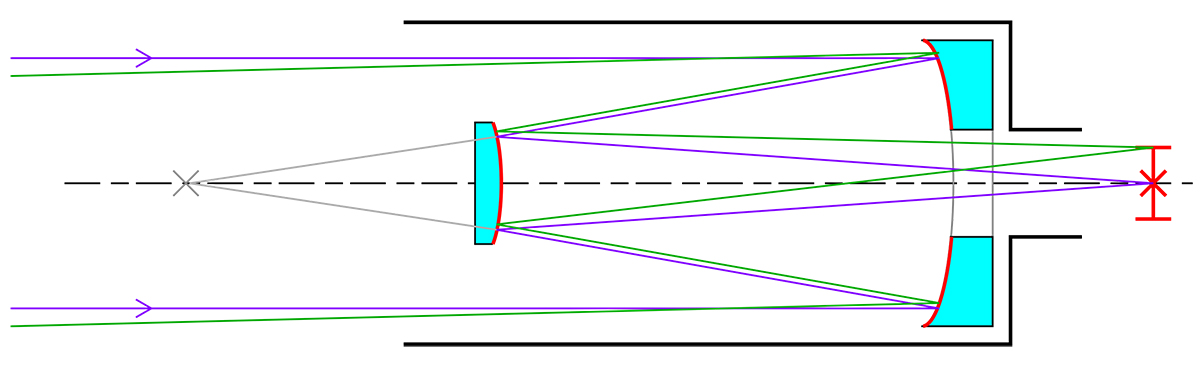

Both Newtonian (top) and Cassegrain (bottom) optical designs use mirrors to reflect the incoming light toward an eyepiece or other detecting instrument.

[Krishnavedala/Wikimedia]

Popularizing astronomy

With crewed space exploration in full force in the 1970s, amateur astronomy became a cultural phenomenon. And the return of Comet Halley in the 1980s brought everyone out to the streets, peering into the sky to see a moment in history.

Some of the modern major telescope makers — whose names might sound familiar, like Celestron and Meade — began mass production. Unfortunately, many of these mass-produced telescopes had significant optical aberrations, making them good enough for a child viewing the sky from her yard, but not fit for serious science.

Some people still couldn’t afford these commercial telescopes. To further bring the cost down, John Dobson, founder of San Francisco Sidewalk Astronomy, in the 1960s built a bare bones reflecting telescope to show the night sky to the public. This simple, scraped-together scope used repurposed materials, and it cradled low to the ground in a small swivel mount. The now-famous Dobsonian telescope design remains popular today.

At the same time, the gulf between professionals and amateurs grew wider than ever. Professionals were beginning to take advantage of new technology, which was far too expensive for an amateur to get their hands on. Photographic plates gave way to new Charge Coupled Devices (CCDs) and CMOS cameras (using compact semiconductors), and research astronomers relied on major telescope facilities to do their work.

The technological divide did eventually close again toward the turn of the century, as cameras and other equipment became cheaper to produce and therefore more widely available. (If you know that CMOS cameras are now what every iPhone uses, you’re one step ahead.) Some astronomy societies now serve this “Professional Amateur” sub-group, such as the Society for Astronomical Sciences. The internet, too, served as an equalizing force, providing amateurs with access to research literature and night sky databases, and provided ways to forge connections with one another even across great distances.

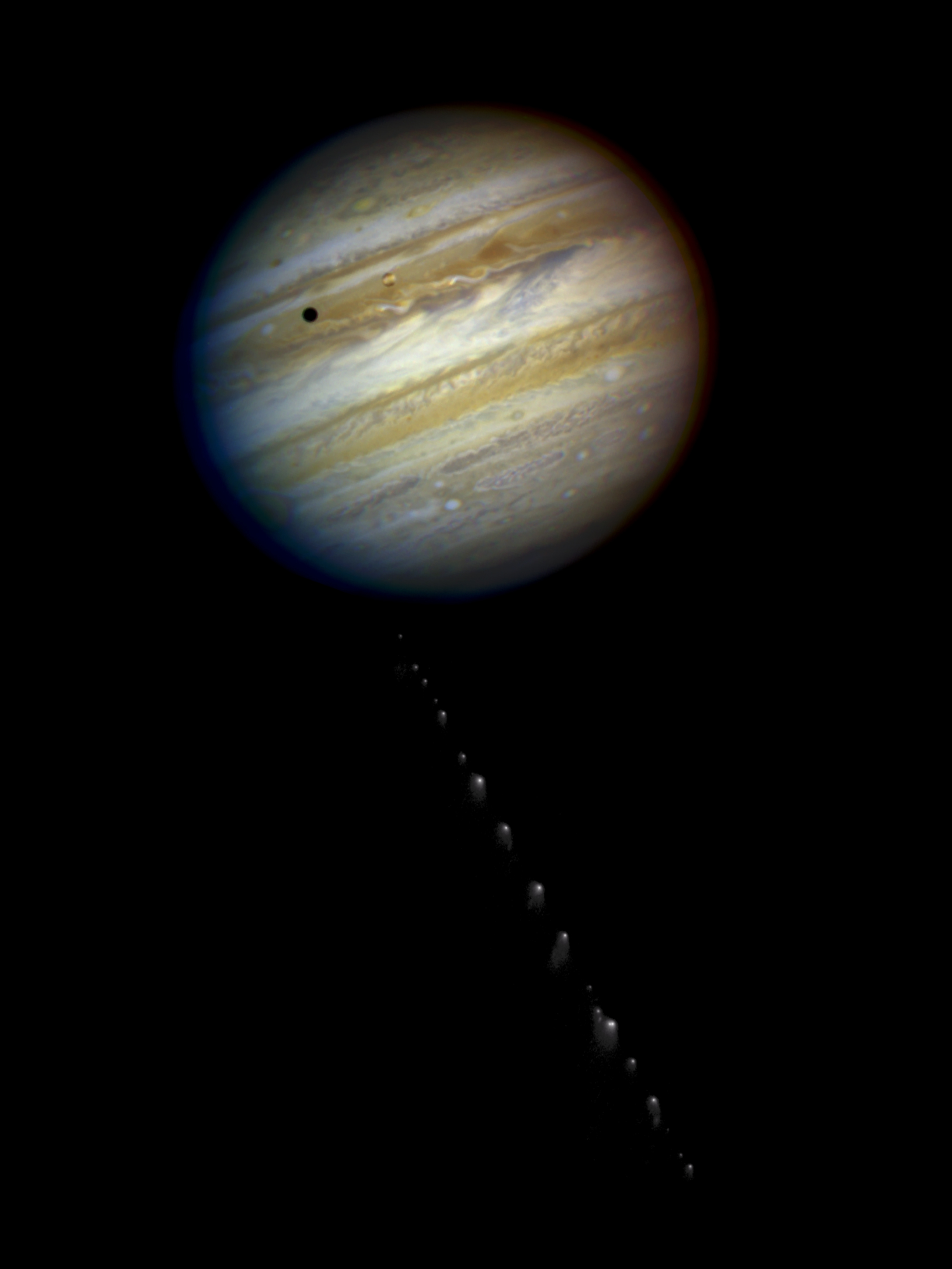

In the past century, amateur astronomers have contributed to some incredible discoveries, including that of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 that crashed into Jupiter in 1994; David Levy was, and still is, an amateur astronomer and comet-discoverer.

The famous Comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp), spotted in 1995, was also co-discovered by an amateur. Thomas Bopp, a construction worker, was observing out in the desert with friends when he spotted it, independently of professional astronomer Alan Hale. Amateurs have contributed to follow-up observations of exoplanets, monitored Jupiter to help with NASA’s Juno spacecraft mission, discovered supernova explosions, cataloged variable stars with the AAVSO, and even found a lost NASA satellite’s signal.

The Dobsonian telescope design is a reflecting scope on an easy-to-move mount. John Dobson introduced the first version of this simpler design in the 1960s.

[Jugger90/Wikimedia]

In 1994, Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 collided into Jupiter. This composite photo, released nearly two decades later, combines separate images of Jupiter and the comet as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope.

[NASA/ESA/H. Weaver and E. Smith (STScI)/J. Trauger and R. Evans (Jet Propulsion Laboratory)]

Science among society

Today, the landscape of amateur astronomy in the U.S. hosts a wide spectrum of participants — from those with a passing interest, to casual observers like families with simple backyard telescopes, to dedicated star-party-hosting recreational observers, to those serious amateurs who focus on making scientific observations. This is the reason why the term “amateur astronomers” doesn’t do the community justice: there are so many ways to be an astronomer, other than to have it as your PhD-educated career.

“Amateur astronomy clubs have always been — and are still — a place for enthusiasts to come together to share their love of astronomy with each other, to learn new skills, to hear about the latest astronomical discoveries, and to mentor newcomers to the hobby,” says Rick Fienberg, Senior Contributing Editor at Sky & Telescope magazine and former AAS Press Officer of the amateur astronomy community today. “In addition to clubs, there are organizations that bring amateurs and professionals together to advance the science of astronomy, something that amateurs are better able to do now than at any previous time, thanks to the immense power of digital detectors coupled to computer-controlled telescopes. The internet, listservs, and social media have made it possible for amateurs worldwide to be in regular communication with each other, sharing images, observing tips, livestreams of eclipses and other events, and more. While in the past you might know only other amateurs in your local area, now you can interact with amateurs (and professionals) worldwide.”

Amateurs are receiving more recognition from professional organizations, too. Public engagement is a core part of NASA’s mission, and the space agency supports efforts across the country to share new astronomy discoveries and the joy of the night sky, such as through NASA’s Solar System Ambassadors program. The AAS recently added an “Amateur Affiliate” membership category in 2018, and the organization hosts the Chambliss Amateur Achievement Award for outstanding contributions to the field from an amateur astronomer.

Plus, astronomy-interested folks who don’t have their own telescope can contribute to scientific research now through what are called citizen science projects. In these, online platforms like Zooniverse allow anyone with internet access to help sift through research data to answer questions about planet formation, galaxy evolution, and more.

Amateur astronomy, in all its forms, is thriving in the U.S. The country has around 600 amateur astronomy clubs, which host public lectures from expert guest speakers, provide telescope viewings for school groups, help budding observers learn how to operate scopes, and more.

Dozens of amateur astronomers set up their telescopes for a public star party at the Grand Canyon National Park.

[NPS photo/Michael Quinn]

Chuck McPartlin, outreach coordinator for the Santa Barbara Astronomical Unit, describes how valuable he’s found his time in amateur astronomy. “For me, it’s been very rewarding to meet and interact regularly with all the cool, interesting, smart people the club attracts,” he says. “Sharing the night sky with them and with the general public to try to get more people interested in science is very gratifying.”

Although it has a winding history, at its core amateur astronomy is all about community — finding people who enjoy the same things you do and who also share that joy with others. It’s a reminder that you don’t have to be a professional to be a scientist, as long as you look at the world with scientific curiosity. Anyone can be a scientist, and maybe they’ll even be inspired by their local astronomy club. ✰

(Originally published March 31, 2023)

BRILEY LEWIS is a freelance science writer and also a Ph.D. candidate and National Science Foundation Fellow at the University of California, Los Angeles, studying astronomy & astrophysics. Follow her on X @briles_34 or visit her website www.briley-lewis.com. She thanks Michael Marotta (AAS HAD), Samantha Thompson (AAS HAD), Rick Feinberg (AAS), Chuck McPartlin (SBAU), Tom Totton (SBAU), Jerry Wilson (SBAU), Ron Herron (SBAU), and Bart Fried (AAA) for their help regarding this article, pointing her to valuable resources, and sharing their knowledge and experience.

Mercury is an advertisement-free publication. If you are interested in supporting Mercury, please email us.