History & Culture

Annals of Astronomy:

Discovery of the Sun’s Rotation

Observations of sunspots were integral in understanding the rotation of our star.

By Clifford J. Cunningham

NSO/AURA/NSF

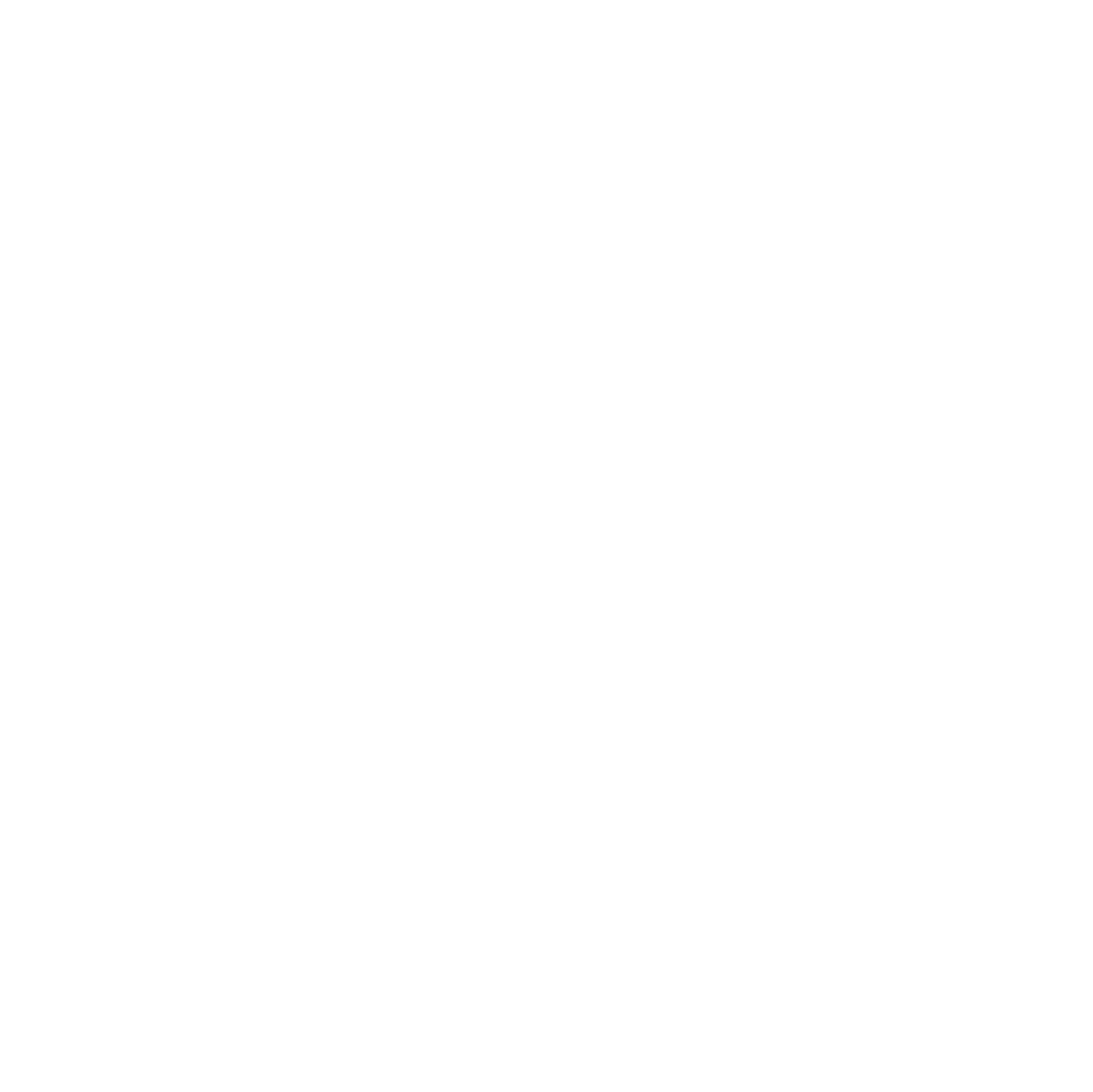

Four-hundred years ago, Jean Tarde believed sunspots were planets moving across the Sun. He drew this sketch of what he saw on the Sun.

[Jean Tarde, Borbonia Sidera; Wikimedia.org/JeeringElk1]

The discovery of sunspots in 1610 led to an even greater discovery: the rotation of the Sun itself.

In the Winter 2018 issue Mercury, I wrote about sunspots as they were understood in the 18th and early 19th centuries. This column will look at the century in which sunspots were first studied.

While some very large sunspots were seen before the telescope was invented (John of Worcester drew sunspots in the year 1128 and Johannes Kepler saw one in 1607), their discovery is attributed to Thomas Harriot, while observing in England with one of the first telescopes. He noted their appearance in December 1610, but did not publish his finding. The 24-year-old Johannes Fabricius was the next to see sunspots, likely in March 1611. After several weeks of tracking sunspots, Fabricius was the first to prove the Sun rotates. His observations, which he made near Osteel in modern-day Germany, were published on June 13 that year, but as he was young (and died just five years later) it was easy to ignore him. Galileo made his first sunspot observation on June 2, 1612, and when his study of them was published in Rome in 1613, Fabricius was not mentioned. Also ignored was Giordano Bruno who stated in 1591 (based on his idea of chemical changes in its liquid parts) that the Sun rotates.

In the meantime, a Jesuit mathematics professor, Christoph Scheiner, also saw sunspots and got into a long-running dispute with Galileo as to who should claim priority of discovery and the nature of what they saw. One of their few points of agreement was completely ignoring Fabricius, but a 1621 book by Robert Burton of Oxford University gives credit for solar rotation entirely to Fabricius.

The nature of sunspots (a word first used in the early 19th century) was a lively topic for centuries. Jean Tarde (who named them Sidera Borbonia in 1620) and Charles Malapert (who called them Sidera Austriaca in 1619) thought they were planets moving about the body of the Sun. Galileo was the first to correctly determine they were on the Sun, not orbiting around it.

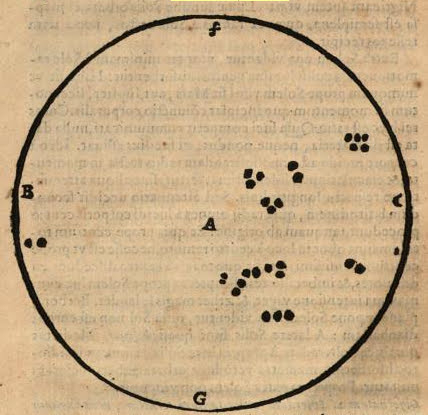

NASA

Sunspots, the dark areas in this image, are regions of cooler material.

[NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/SDO]

“Spots are observed in that which bounds the Year” charmingly wrote the poet Edward Waller in the 1680s, in the midst of an era when sunspots were rare. In what is now called the Maunder Minimum, named after the nineteenth century scholar Edward Maunder, virtually no sunspots were seen from 1645 to 1715. It appears the first literary reference to the absence of sunspots was made in 1667 by the English poet Andrew Marvell. We owe the discovery of this to a scientist who studied sunspots as the best way to understand the magnetohydrodynamic behavior of the Sun. Nigel Weiss of Cambridge University, who died in 2020, and his wife Judy, a scholar in English, published a paper in 1979 in which they described a political satire by Marvell. Prepared in 1667, it is written from the viewpoint of a sentient Sun, who is quite pleased by his spots. However, astronomers regarded them as blemishes, and when the Sun became aware of this, it cast them away! In this coded language, Marvell was urging King Charles II to cast off his corrupt courtiers, who were damaging the monarchy.

CLIFFORD J CUNNINGHAM was recently interviewed about asteroids on a U.S. nationally broadcast radio show hosted by physicist Dr. Michio Kaku.

There was a notable exception to the dearth of sunspot sightings: Their return was heralded four years after Marvell’s poem, in a 1671 paper published in the Philosophical Transactions in London. “It is now about twenty years since, that astronomers have not seen any considerable spots in the Sun.” The paper related observations made by Giovanni Cassini in Paris, who saw three sunspots, one in “the shape of a Scorpion.” Based on just three days of observation, Cassini arrived at a solar rotational period of “twenty seven days and a half.” This was much slower than the period of 24 hours adopted by Kepler, but the speed race was “won” by Otto Guericke. In a rather tongue-in-cheek way, Edward Sherburne wrote in 1675 that Guericke assigned to the Sun “a much more wonderful celerity, and affirming its vertiginous course to be finished in a moments space.”

There is no “correct” figure for the rotational period, as the Sun is not a solid object; as discovered by Scheiner and written in a book published in 1630, the rotation rate at higher latitudes is slower. Modern data show this differential rotation varies from 24.47 days at the equator to 36 days at latitude 80 degrees, so the latitude of sunspots (not seen above 50 degrees on the Sun’s photosphere) will result in differing values. ✰

Mercury is an advertisement-free publication. If you are interested in supporting Mercury, please email us.